- Latest Legal News

- News

- Dealstreet

- Viewpoint

- Columns

- Interviews

- Law School

- Legal Jobs

- हिंदी

- ಕನ್ನಡ

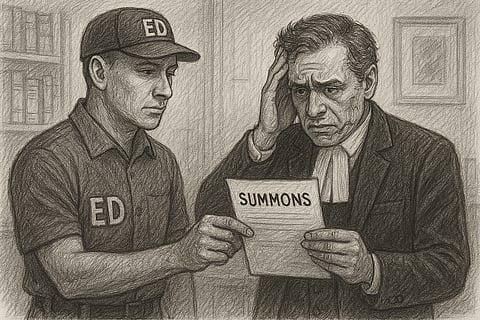

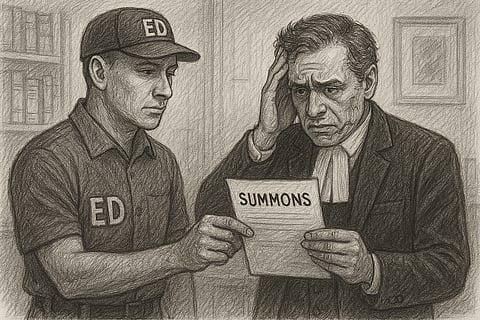

When the Enforcement Directorate (ED), India’s anti-money laundering agency, sent notices to Senior Advocates Arvind Datar and Pratap Venugopal - two of the country’s most respected legal voices - it triggered more than professional discomfort; it set off constitutional alarms. These weren't merely summons. They were a signal.