- Latest Legal News

- News

- Dealstreet

- Viewpoint

- Columns

- Interviews

- Law School

- Legal Jobs

- हिंदी

- ಕನ್ನಡ

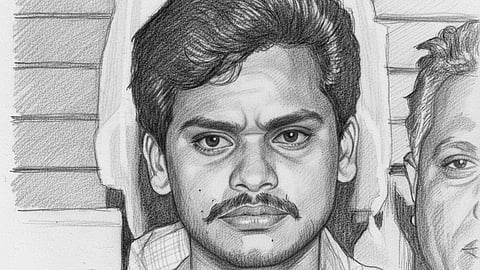

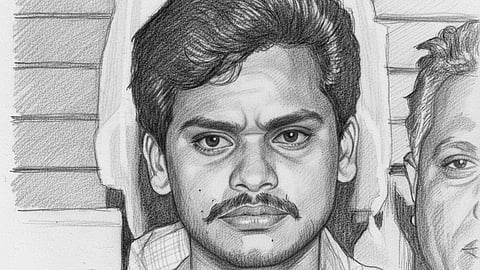

Every now and then, a criminal case collapses not because the accused is proved innocent, but because the State fails the test of proving guilt lawfully. The Supreme Court’s judgment in Surendra Koli v. State of Uttar Pradesh is one such example - a verdict in a curative petition that quietly unravels what was once treated as a closed chapter.