- Latest Legal News

- News

- Dealstreet

- Viewpoint

- Columns

- Interviews

- Law School

- Legal Jobs

- हिंदी

- ಕನ್ನಡ

The deep permeation of technology in the last decade has touched every aspect of public life, including the judicial system. With the Supreme Court’s decision to live-stream its proceedings, coupled with a rise in specialised court reportage, the Court has become accessible to the public in unprecedented ways.

Its proceedings are now a regular feature in the news and are often the subject of public discussion. To borrow the words of a former Chief Justice, the Court is now in the "homes and hearts of the people".

This increased visibility means that when the Court speaks, its words are closely scrutinised, and accorded significant weight. Such influence brings with it a corresponding duty: the Court must remain circumspect in making observations, particularly given the risk that they may be taken out of context or deployed for extraneous purposes. Recent instances of judicial remarks being used for political ends suggest a need for introspection.

The Supreme Court has always been a central actor in moments of political turbulence, given its wide constitutional powers to review government action and fashion far-reaching remedies. However, the Court’s new prominence in public discourse has led to a phenomenon where political actors selectively rely on judicial observations to target their opponents.

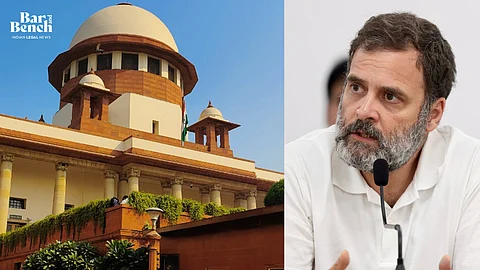

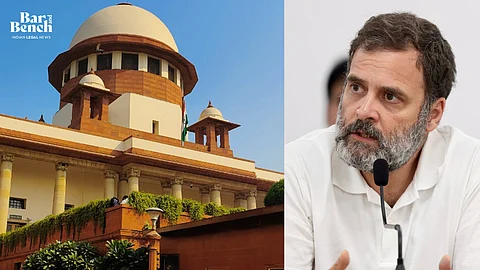

A recent example concerns observations made by a Bench of the Supreme Court while hearing an appeal by the Leader of the Opposition, Rahul Gandhi, against summons issued in a defamation case. The complaint, filed in 2022, alleged defamation arising from his remarks on a clash between the Indian and Chinese armies. The summons, first challenged unsuccessfully before the Allahabad High Court, were then assailed before the Supreme Court. The legal question was narrow: whether Gandhi was entitled to a stay of the proceedings. The Court found prima facie that he was, and granted the stay.

However, the Bench also made certain observations that were not directly connected to the question before it. These included remarks questioning Gandhi’s patriotism ("a true Indian will not say this"), suggesting that such matters should be raised in Parliament, and challenging the credibility of his statements. Such comments, unrelated to the lis and unnecessary for the adjudication of the stay application, could have been avoided. In the Court’s own jurisprudence, adverse remarks against parties should be made only when essential to the resolution of the dispute, particularly in the era of live-streaming where judicial words have an immediate and wide impact. In a case, the Court has observed,

“It is essential for the courts to be extremely cautious while passing adverse remarks against the parties involved, and must do so with proper justification, in the right forum, and only if it is necessary to meet the ends of justice.”

More significantly, these observations were subsequently invoked in political discourse. Members of the ruling party cited them to criticise Gandhi, describing his party as “the biggest violators of constitutional values” and labelling him “a certified anti-national”. In effect, the Court’s remarks became instruments in political contestation – a development the Court has historically cautioned against. In the context of Public Interest Litigation, for instance, the Court has emphasised that its process must not be used for political objectives, holding that petitions motivated by such aims constitute an abuse of judicial process. In SP Gupta, the Court observed:

“The court must not allow its process to be abused by politicians and others to delay legitimate administrative action or to gain a political objective.”

Yet, despite reiterating such principles, the Court’s own remarks have, in recent times, facilitated a trend in which they are misused for political gain.

Judicial remarks, when used appropriately, are an important part of court proceedings. They clarify issues, enable counsel to refine arguments and assist the Bench in exploring competing positions. As the Court itself has recognised, exchanges from the Bench are intrinsic to transparent adjudication and can aid persuasion. Yet, this must be balanced by judicial restraint. Remarks should remain related to the issues in dispute and avoid unnecessary personal comment that risks reputational harm. The Court has acknowledged that "the power of judges must not be unbridled" and that strong or scathing language should be employed only when strictly warranted.

An instructive contrast emerges from two recent matters. In one, a Bench led by the Chief Justice of India BR Gavai dealt with a plea to protect Veer Savarkar’s name under the Emblems and Names (Prevention of Improper Use) Act, 1950. Without making any broader historical or political observations, the Court simply asked the petitioner which fundamental right had been violated and, finding none, dismissed the plea. By contrast, in another matter concerning Rahul Gandhi’s remarks about Savarkar, the Court, while ultimately granting him relief on legal grounds, offered extended observations on freedom fighters, including a reference to Gandhi’s grandmother. These remarks were not necessary to the decision, particularly as the Court acknowledged that he had ‘made a good point on law and are entitled to a stay.’ However, the Court’s unconnected remarks were once again used to score political grounds. These unconnected observations were again invoked in the political sphere, illustrating the recurring use of judicial remarks for partisan advantage.

It is imperative that the Court remains conscious of the potential political use of its observations and exercises corresponding restraint. Such discipline will help ensure that its processes are not co-opted for partisan advantage. This extends beyond the Bench: law officers and litigants should also be reminded of their responsibility to prevent the misuse of judicial proceedings.

Swapnil Tripathi is the Lead at Charkha (Centre for Constitutional Law) at Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy. Views are personal.