- Latest Legal News

- News

- Dealstreet

- Viewpoint

- Columns

- Interviews

- Law School

- Legal Jobs

- हिंदी

- ಕನ್ನಡ

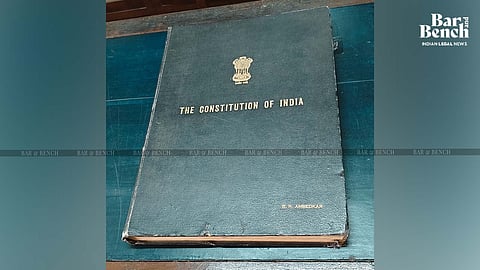

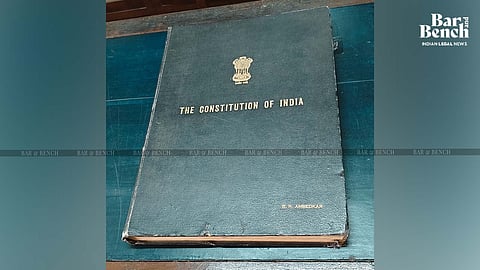

The library at Siddharth College in South Mumbai, a few metres away from the Bombay High Court, has a black‑covered book embossed in gold – “The Constitution of India.”

At first glance, it looks like any other old government volume. Then the name on the bottom right comes into view, “Dr. B R Ambedkar”, and it is clear this is no routine edition.