- Latest Legal News

- News

- Dealstreet

- Viewpoint

- Columns

- Interviews

- Law School

- Legal Jobs

- हिंदी

- ಕನ್ನಡ

The Securities Appellate Tribunal (SAT) recently delivered a scathing indictment of the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) in Rajesh Mokashi v. SEBI, dated June 27, 2025.

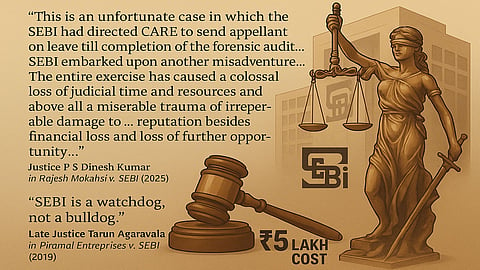

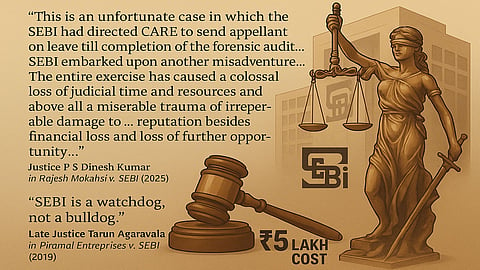

The Tribunal quashed a SEBI order debarring Rajesh Mokashi, former MD and CEO of CARE Ratings, from associating with any SEBI-registered intermediary. The judgment, which imposed costs of ₹5 lakh on SEBI, panned the markets regulator for wasting judicial time pursuing the case.

At the heart of the matter are whistleblower complaints from December 2018, alleging that senior officials at CARE Ratings, particularly Mokashi and hen Non-Executive Chairman SB Mainak, interfered with the credit rating process to benefit clients paying higher fees. These were related to instruments issued by Dewan Housing Finance Ltd (DHFL), Yes Bank Ltd (YBL), Infrastructure & Financial Services Ltd (IL&FS) and certain other companies. These allegations prompted SEBI to instruct CARE to conduct a forensic audit.

Ernst & Young LLP was brought in for this purpose, and following its forensic audit report, SEBI advised another full-fledged inquiry. CARE turned to former Supreme Court judge Justice BN Srikrishna to lead the investigation. His findings were also unequivocal: there was no evidence to support the claims of interference or misconduct by either Mokashi or Mainak.

Notwithstanding these conclusions, SEBI proceeded to issue show cause notices to both individuals. The final order, dated April 20, 2023, presented an odd juxtaposition. It exonerated Mainak, while simultaneously debarring Mokashi for two years, relying heavily on WhatsApp messages and interpretive circumstantial evidence. What made the action more curious was that the same evidence, reviewed by both Ernst & Young and Justice Srikrishna, had previously led to a clean chit for both parties.

While Mainak was begrudgingly exonerated by SEBI due to "non-availability on record of adequate and sufficient evidence to conclusively prove the involvement," Mokashi was left to face an enforcement action that, as the SAT later pointed out, lacked legal and evidentiary integrity.

The SAT’s judgment is notable not merely for its outcome, but for the language it uses. The ruling states,

“SEBI embarked upon another misadventure to conduct one more proceeding through its WTM...the entire exercise has caused a colossal loss of judicial time and resources and above all a miserable trauma of irreparable damage to appellant’s reputation besides financial loss and loss of further opportunity to him.”

The Tribunal found that SEBI had fundamentally misconstrued the Srikrishna report. SEBI had brought a technical argument that Justice Srikrishna merely examined whether the alleged interference affected the final rating outcome. However, SAT clarified that this was a complete mischaracterisation and distortion. The report, in fact, squarely addressed whether Mokashi interfered at all, and categorically concluded that he did not. Worse, SEBI’s attempt to suggest that it had the “benefit” of cross-examination that Justice Srikrishna did not, was dismissed as “reprehensible.” Witnesses, when cross-examined by SEBI, had offered clear denials of any pressure or instruction from Mokashi. One of SEBI’s own key witnesses admitted that rating decisions were taken on a consensus basis and that no dissent had ever been recorded.

Ironically, such judgments often prompt a regulator to send its officers for a week or two stints at judicial academies or observational visits to foreign regulators, a gesture more symbolic than substantive. At the same time, the deeper purpose of building institutional mechanisms for fairness and accountability is lost in the absence of meaningful reflection.

This case is not a standalone episode. It is part of a pattern that has played out in multiple recent decisions where the SAT and the courts have had to step in to restrain SEBI’s overreach. In previous cases too, SAT, the Bombay High Court and the Supreme Court of India have expressed concern over the regulator’s conduct. Bar & Bench has chronicled these developments in a series of articles: SAT imposes costs on SEBI for passing another mechanical order; Imposition of costs: A tussle between SAT and SEBI; Playing with fire: SEBI apologizes to the Supreme Court of India in contempt proceedings; and Judicial Scrutiny of SEBI: An Obstinate Regulator? The Supreme Court’s caution in RT Agro Pvt Ltd v. SEBI (2022) is instructive: regulators must not adopt hyper-technical postures in enforcement. SEBI, in multiple instances, has refused to course-correct, even in the face of stern judicial nudging. It has continued to pursue matters on tenuous procedural grounds, appealing almost every adverse order to the Supreme Court, while often dismissing substantive exculpatory material in favour of selectively applied evidence.

In the Mokashi matter, the regulator’s insistence on framing its case around a few internal messages, while dismissing the absence of any formal dissent, appears emblematic of an enforcement culture that has, at times, prioritised optics over objectivity. SEBI’s role is not merely to enforce, but to enforce with fairness and proportion. By brushing aside the conclusions of various reports without introducing any new facts or analysis, SEBI not only undermined its own institutional integrity, but also demonstrated a troubling inability to self-correct.

In view of the recent SAT decision and others before it, there is a need for a reassessment of how SEBI approaches quasi-judicial functions and how it treats independent findings when they do not suit its narrative. The call for reform is not new. The lack of clear procedural codification - especially regarding how evidence is appreciated, how cross-examination is treated, and how defence submissions are evaluated - has led to inconsistent and frequently overturned orders. There is an urgent need for standardisation, and perhaps more importantly, for a new regulatory architecture to approach matters with procedural rigour and neutrality.

The message of institutional restraint and procedural fairness resonates far beyond SEBI. The United States Supreme Court recently, in SEC v. Jarkesy (2024), delivered a landmark 6-3 verdict questioning the constitutional legitimacy of enforcement actions conducted by administrative law judges without sufficient safeguards. The Court held that when the US SEC seeks civil penalties for securities fraud, the Seventh Amendment of Constitution guarantees the right to a jury trial. Consequently, the ruling effectively stripped the SEC of its ability to unilaterally route such matters through in-house Administrative Law Judges (ALJs), thereby requiring adjudication in federal courts.

While India’s regulatory structure may differ in form, the underlying concern - ensuring fairness in administrative adjudication - is a universal imperative that demands comparable scrutiny and reform. In the Adani-Hindenburg Saga, an Expert Committee constituted by the Supreme Court had also critiqued ‘the lack of separation’ between the investigative and adjudicatory functions, noting that this compromises institutional fairness and objectivity. The report submitted by the Committee had suggested that "a structural reform is needed to separate the investigative and adjudicatory wings. This will promote fair hearing, natural justice, and reduce the perception of bias".

SEBI wields enormous power, and rightly so. In a market-driven economy, safeguarding investor interests and upholding market integrity is a non-negotiable imperative. But enforcement is not an end in itself. It must be exercised with restraint - anchored in due process, transparency and proportional justice. This becomes all the more critical when an institution acts as judge, jury and executioner.

The late Justice Tarun Agarwala articulated this with memorable clarity in Piramal Enterprises Limited & Ors v. SEBI (2019), reminding us that “SEBI is a watchdog, not a bulldog.” That dictum is not just apt, it is urgent.

Regulatory power, no matter how well-intentioned, is not immune from scrutiny. Institutions must remain tethered to the rule of law. Whole Time Members (WTMs) and senior functionaries of regulatory bodies are subject to legal accountability. And when justice is obstructed by bureaucratic intransigence, it must nevertheless be pursued with clarity and courage, at any cost.

Yet, if precedent is any guide, SEBI’s likely response will not be introspection, but escalation. SEBI’s institutional muscle is rarely accompanied by institutional humility. When called out, it does not reform, it appeals. Expect a Special Leave Petition, a plea to expunge, or a stay application. In a system where courts often extend leeway to regulators, SEBI has grown comfortable relying on judicial deference, not internal reform.

Let’s hope the new SEBI Chairman breaks this cycle.

Sumit Agrawal is the Managing Partner, Regstreet Law Advisors, a former SEBI Officer and an author of a book on SEBI Act. The article was authored with assistance from Kavish Garach, a Senior Associate.

The views expressed are personal.

Disclosure: The author represented Mainak before SEBI.